I have admittedly always felt ambivalent about Pride Month. I am perfectly happy to be gay, but it seems odd to me to be proud of something I had no control over. I wouldn’t say I’m proud to be white, male, a millennial, or a native English speaker. I’m not ashamed of any of those things, and they’ve all shaped my life in meaningful ways, but they are simply accidents of my birth. Taking pride in them seems like a category mistake.

To be fair, being an American is also an accident of birth, and yet we understand what it means when someone says they are proud to be an American. It means that they are proud of their country’s ideals, proud of its historic accomplishments, and proud of its influence around the world (at least much of the time). As long as it leaves room for needed criticism and doesn’t descend into jingoism, a certain amount of national pride can be quite healthy for social cohesion, as it tethers a diverse population to a core shared identity.

The positives of Pride

The best case for pride based on sexual orientation or identity is somewhat similar. For many gay, bisexual, and transgender people, the concept of pride feels like a necessary rejoinder to the ingrained narrative that those identities should be a source of shame. Simply saying that it’s okay to be gay (or bi or trans) can feel like an inadequate antidote to a lifetime of internalized shame. For many, something stronger and more celebratory feels called for.

And just as someone can reasonably take pride in their country’s achievements, it also makes sense to say that you are proud of the bravery of generations past who came out before you and, in much more challenging times, changed hearts and minds on a remarkable scale. Today, too, many gay, bisexual, and transgender people continue to face serious obstacles upon coming out—especially within the church—and taking a measure of pride in one’s resilience in the face of adversity can be a good thing.

And yet: There are limits on how much the concept of pride as it relates to sexual identity is constructive. Pride, of course, has multiple meanings, one of the best-known of which is seriously negative: overinflated self-regard. That is the sort of pride the Bible warns against as a sin, and for that reason alone, “pride” isn’t the word I would’ve gone with had it been up to me at the start of the gay rights movement. (But I wasn’t alive then, so that’s beside the point.)

To be clear, most LGBTQ people do not use the word in this way, just as most parents who say they’re proud of their children aren’t using it in the biblical sense either. But as the maxim in politics goes, if you’re explaining, you’re losing, so I don’t love leading with a term that is so vulnerable to misinterpretation.

Moreover, the perils of misconstrual aside, pride based on sexuality doesn’t have the same salutary social effects as pride based on nationality. Most people in one’s local community share a national identity, so taking pride in being an American—or a Canadian, or a Swede, or a Brazilian—can help bring everyone together around a common sense of purpose and values. But pride based on characteristics that only some of the population possesses, by contrast, typically connects only that portion of the population together.

That isn’t necessarily a bad thing. When a minority group needs to gain or defend its rights, putting a certain amount of focus on their shared identity can be an important part of mobilizing to effect change. That was especially true for the gay rights movement, as many gay people wouldn’t have known they weren’t alone if it weren’t for the greater visibility things like Pride helped create. So I understand the strong attachment many have to Pride: it has played a positive role in advancing awareness and acceptance over the years.

The backlash to Pride

More recently, though, we’ve seen a growing backlash to Pride. There are various reasons for that development: the increased salience of controversial topics like transgender participation in women’s sports and medical transitions for minors, high-profile examples of inappropriate behavior at Pride events (see below), and a general exhaustion with what’s felt to many like oversaturation of the media market with all things LGBTQ every June, to name a few.

Fundamentally, though, the backlash to Pride is a function of the fact that it is focused on the celebration of identities that are not universal. It was briefly able to unify a broad cross-section of the country (circa 2010-2020) when it was primarily associated with a cause—namely, same-sex marriage—that anyone could support. It was thus able to bring together a remarkably diverse group of people in the name of a shared goal. But once that goal was accomplished, Pride’s ongoing purpose gradually became less clear, and ideological infighting picked up steam. Could lesbians who support Israel be included at the Dyke March? Was there still a place for gay police officers who wanted to march in uniform? The answers, according to the activists who were increasingly steering the ship, were no and no.

As new litmus tests were added, the original Pride flag began to undergo various permutations, each one seeking to highlight additional subgroups within the broader LGBTQ population. The acronym itself expanded accordingly: from LGBT to LGBTQ, then LGBTQ+, then LGBTQIA+, then even 2SLGBTQIA+, which is now the official acronym used by the Canadian government. This ever-evolving label has grown so unwieldy that it has spawned tongue-in-cheek comparisons to a Wi-Fi password. It certainly doesn’t roll off the tongue.

But ironically, despite the noble aim of making Pride more inclusive, these shifts often achieved the opposite result in practice. By adding issue after issue to Pride’s public platform, a large number of gay, bisexual, and transgender people who once felt fully welcomed increasingly sensed they were now out of place. In certain circles, that alienation extended not only to pro-Israel lesbians or gay cops, but to anyone who argued (quite reasonably) that publicly celebrating kinks and making Pride family-friendly are mutually exclusive goals.

The “queer” shift from integration to rebellion

Over time, Pride’s center of gravity thus shifted toward activists who no longer represented the average gay, bisexual, or transgender person. Instead of maintaining the historic focus on shared values—like love, commitment, and family—that had transformed public attitudes toward LGBTQ people and made marriage equality a reality, these activists increasingly began to scorn that legacy and the values it was built on.

As Chase Strangio, a high-profile transgender activist, wrote in 2022:

“I feel an inexplicable amount of rage witnessing the Senate likely overcome the filibuster to vote to codify marriage rights for same-sex couples.”

These words wouldn’t have been shocking to hear from a conservative Christian activist, but from someone in a key leadership position within the LGBTQ movement, they were head-turning indeed. Strangio explained that the institution of marriage was “fundamentally violent” and that “the mainstream LGBTQ legal movement caused significant harm in further entrenching the institution of marriage as an organizing structure of US civil society.”

This is a fringe perspective, to say the least, and the vast majority of gay, bisexual, and transgender people themselves do not share it. That said, it does represent a school of thought that has long been an uncomfortable fellow traveler with the mainstream LGBTQ movement. This more radical, anti-normative philosophy was given formal expression through the emergence in the 1980s and 1990s of an academic field called queer theory. I have been sharply critical of queer theory because I regard its core claims as false and profoundly counterproductive.

To name a few: that all social norms are inherently oppressive, that calling yourself “gay” or “bisexual” is a naive and futile reconstitution of the suffocating power of labels, and that LGBTQ people should not seek to be integrated into society and its institutions but should instead seek to subvert, or “queer,” them.

“Queer,” within the framework of queer theory, does not simply mean “not straight.” Queer theorists use it much more sweepingly to describe anything and everything that contravenes social norms. So a heterosexual person can be “queer” in this configuration if they simply reject monogamy, for instance, or have a penchant for exhibitionism, public sex, or any other socially disapproved fetishes. All such disapproval, for the queer theorist, is an intolerable weaponization of power against the marginal “other.”

Some may wonder if queer theory can actually be as out there as critics like myself claim. I appreciate such skepticism because it is a sign that the skeptic holds reasonable beliefs themselves and therefore struggles to imagine how highly intelligent people could actually think these things. Unfortunately, some of them do, and I would encourage you to read the works of Gayle Rubin, Judith Butler, Michael Warner, and other queer theorists if you want to see the primary source material for yourself. (Though I should warn you that, even by the standards of academic writing, their work can be remarkably opaque.)

Trading persuasion for provocation

Fortunately, queer theory largely remained confined to graduate seminars at elite universities for the first two decades of its existence. But in the early 2010s, some of its precepts began to gain traction among a subset of young people on Tumblr, and by the late 2010s and early 2020s, the outrage-fueled algorithms of social media enabled it to make a fateful leap to the masses. Simultaneously, its knee-jerk anti-normative ethos began to reshape the messaging of the LGBTQ movement, inspiring high-profile activists to adopt an increasingly aggressive, holier-than-thou posture toward the third or so of the country that still disapproved of same-sex relationships and transgender people.

These activists no longer sought to persuade those who disagreed through reasoned argument. Whereas leading advocates for same-sex marriage had broadly welcomed the opportunity to debate the topic, confident in the strength of their arguments, this new cohort of LGBTQ activists who drank from the well of queer theory embraced the motto of “no debate.” Many of them then went out of their way to cause needless offense to broad swaths of the country.

Among numerous high-profile examples:

The Los Angeles Dodgers sparked outrage when they bestowed a Community Hero Award on the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence in 2023. The Sisters are drag queens who dress up like nuns and openly mock Christianity. They do community service, which is good, but they are also infamous for a hypersexualized “hunky Jesus” contest that has involved public portrayals of “Jesus” engaging in sex acts. (If you don’t believe me, this is a not-safe-for-work YouTube video of the contest; the behavior of the “winner” is so offensive that it would appall many non-Christians as well as Christians.) The Dodgers hemmed and hawed but ultimately defended their position by conflating the Sisters with the entire “LGBTQ+ community.” The message—supporting the LGBTQ community means mocking Christians—could not have been better engineered to alienate millions of Americans.

A Dallas gay bar hosted a drag queen brunch called “Drag the Kids to Pride” in June 2022. Despite being advertised as “family-friendly,” the reality looked more like a strip club. Drag queens in sexualized outfits performed inappropriate dances for young children, who were given dollar bills to hand to the performers. The centerpiece of the event was a giant neon sign blaring this very not family-friendly message: “It’s not gonna lick itself!” This event, sadly, was not an anomaly; there were numerous similar incidents of inappropriate conduct at drag queen brunches and story hours targeted to children across the country.

Perhaps most notoriously, a transgender activist who was invited to a Pride event on the White House lawn in June 2023 used the opportunity to take her top off—and then posted a video of it to her own TikTok. To its credit, the White House released a statement condemning her behavior and banning her from future events, but much of the damage was already done. All most Americans saw from the White House Pride event was a flagrant display of public indecency.

Visibility matters, and when what’s being made visible is effectively a middle finger to the majority of the country, that matters, too.

Consequently, it was depressing but not shocking when, starting around 2023, public support for same-sex marriage began to decline for the first time in years. Republican support for marriage equality has taken a particularly sharp hit, falling from 55% to 41% in just three years. And hostility and vitriol toward transgender people has increased dramatically in that same time period.

Whither Pride?

These trend lines are disconcerting for anyone who cares about advancing societal acceptance for gay, bisexual, and transgender people. But fortunately, there is something we can do about it. First and foremost, the LGBTQ movement needs to reclaim the values-based message of integration that persuaded a majority of Americans to support marriage equality in the first place.

That means drawing a clear line in the sand and unapologetically rejecting the queer theory-based radicalism that has so muddled the movement’s message in recent years. In a free country, provocateurs should have the right to express their views, but any movement that wants to maintain public support is foolish in the extreme if it embraces and elevates such figures as its representatives.

When you position yourself against social norms simply because they are norms, when you declare that “queerness” involves ordering your life as a perpetual protest against society, and when you relentlessly push the envelope for the sake of shock value, you are asking for a backlash. What other result could there possibly be? You can either adopt such an approach and accept the social marginality that inevitably follows from it, or you can seek to persuade others based on shared values and pursue a positive vision of integration instead.

That latter approach is what empowered the extraordinary progress of the LGBTQ movement until recently, and the movement urgently needs to embrace it anew today.

But as important as recovering a mainstream message is, it’s also worth considering what the most constructive role for Pride may be in the years ahead. As many advocates see it, as long as anyone is still mistreated for being gay, bisexual, or transgender, Pride will remain essential to celebrate as zealously as possible—and therefore, the current backlash merely calls for a redoubling of our commitment to it today.

I understand that view, but there are two reasons I don’t share it. First, whether social acceptance will increase going forward will depend on the attitudes of the third of the country that remains opposed to same-sex marriage. This portion of the population is disproportionately conservative and religious, and they are the least likely to be persuaded by even the most wholesome of parades.

For conservative Christians in particular, the problem is not a deficit of LGBTQ visibility. As they will readily tell you, they are well aware we exist. The problem is that they overwhelmingly encounter the wrong kind of LGBTQ visibility. If conservative Christians can ever change their minds on same-sex relationships—and I believe they can—it will not be through secular forms of advocacy at all. It will be through relationships with other conservative Christians who have changed their minds while holding onto their core faith beliefs and their love for God, Jesus, and the Bible.

So Pride may have reached its limit in terms of its ability to advance public acceptance, and among conservative Christians in particular, it is arguably doing more harm than good today. But increasingly, it isn’t just alienating conservatives. The erosion of support for same-sex marriage and transgender people in recent years suggests that Pride—at least with its current combination of cultural ubiquity and ideological rigidity—may no longer even be a net positive for retaining support from the middle third of the country either.

The paradox of Pride

As long as Pride is broadly perceived as a rejection of shame on the part of a mistreated minority group, it’s not hard for the average person to view it positively. That can change, however, after a certain threshold of public acceptance has been met. Once the broad majority of society has become accepting of a previously-disfavored group, that group’s continued emphasis on “pride” can start to sound a little different—a little, well, prideful. Regardless of the intention, the message many hear begins to shift from “we aren’t ashamed of who we are” to “actually, it’s better, cooler, and altogether more interesting to be us than to be you.”

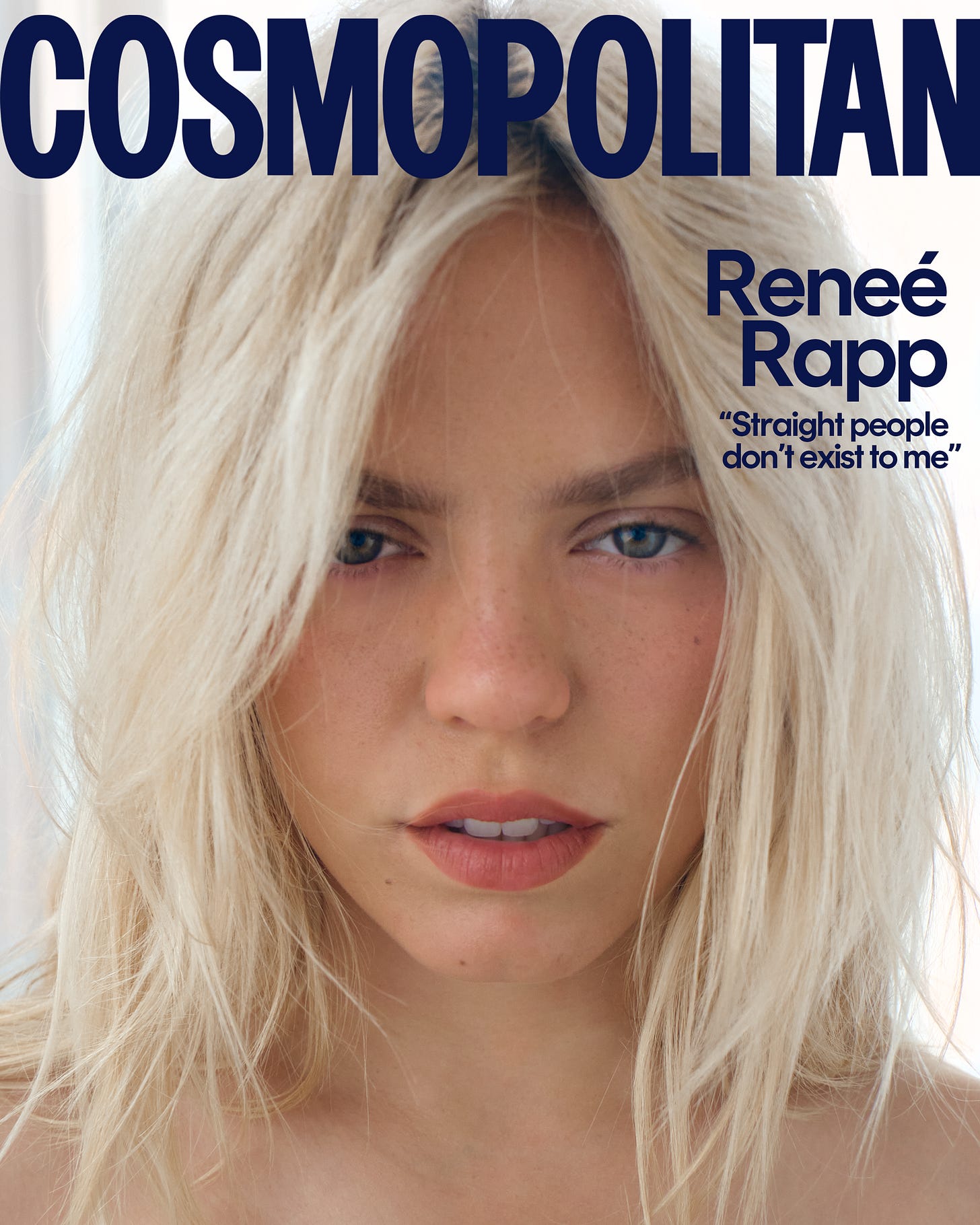

It doesn’t help when LGBTQ celebrities like actress and singer Reneé Rapp say things like this: “Straight people don’t exist to me. I see one and I’m like, ‘What the f**k are you doing here?’ It’s just made my life so fulfilled and so happy.” Or when trans activists go viral on TikTok for statements like this: “Cis-ness is the wound, cis-ness is the delusion, cis-ness is the lie, cis-ness is the place of pain. Transness is the healing, transness is the growth, transness is the truth.”

As head-spinning as it is for anyone born before, say, 2000, there are in fact now schools, peer groups, and subcultures in which being LGBTQ is seen as edgy and cool in contrast to the supposedly vanilla, conformist alternative of being “cishet” (an often pejoratively-tinged portmanteau of “cisgender” and “heterosexual”). To be clear, this is not the case in society at large, where being transgender in particular is far from a plus for one’s social standing. And as the younger cohort of Gen Z shifts to the right, it may prove to be short-lived.

But in recent years, at least, many parents and teachers have reported an unintended consequence of the proliferation of sexual and gender identities now in vogue among adolescents: demisexual, graysexual, agender, bigender, paraboy, demigirl, boyflux, aromantic, alloromantic, genderfluid, trigender, and on and on. While there are young people who feel liberated by this seemingly endless menu of identity options, more of them express some degree of distress about picking a label—and with hundreds of “queer” options now available, they can feel pressure to choose anything other than the default, drab “heterosexual” and “cisgender.”

In that environment, putting an emphasis not merely on accepting everyone but on specifically celebrating students who are not heterosexual boys and girls can create perverse incentives for young people to look for any way to fit under the broad LGBTQ+ umbrella. And given the remarkable capaciousness of many new identity categories (who decides who is truly “trigender”?), almost anyone can if they want to now.

But feeling pressured to conform to non-conformity—to fit oneself into the box of not fitting into boxes—isn’t actually progress. It’s just a mirror image of some of the exclusionary attitudes the gay rights movement initially set out to change. For a real-world illustration of this dynamic, look no further than the shameful hounding of “Heartstopper” actor Kit Connor and author Alice Oseman for not identifying as LGBTQ. Under intense social pressure, Connor came out as bisexual and Oseman came out as asexual. “I’m bi,” Connor wrote. “Congrats for forcing an 18-year-old to out himself.”

The idea that a young person could ever be bullied for not saying they are gay or bisexual almost beggars belief to anyone in their 30s or older. And to be sure, it is still vastly more common for people of all ages to be bullied for not being straight instead. But a movement whose original purpose was to counter shame based on sexual orientation should be very concerned if its apparent progress even inadvertently contributes to people being shamed based on—of all things—their (presumed) sexual orientation.

Until very recently, history has been terribly cruel to people who are gay, bisexual, or transgender. Although recent generations have made enormous progress toward changing that, there is a still a long way to go toward acceptance and equality throughout most of the world. But precisely because much important work remains to do, it’s important to be willing to ask if the movement’s current approach is actually advancing its goals.

We desperately need to recover our ability to make real progress again. But getting there will require the LGBTQ movement to look inward, excise the radical forms of activism that have so diluted its message, and return to the appeal to common humanity that once made it so successful. Doing so would go a long way toward cooling our current culture wars, and it would indeed be something to be proud of.

This is such an important message and so refreshing to see a high-profile person saying what’s been painfully clear for many years: the LGBTQIA2SL+ rights movement has become one of the biggest threats to lasting LGBT rights.

This is brilliant Matthew! I’m SO glad you’re talking about this. I’ve been feeling rather frustrated at the silence on this topic within many affirming Christian circles. There seems to be a total capitulation to left wing politics in much the same way that the conservative Christian community has capitulated to right wing politics! I’m so grateful for your voice on this! Have you by chance heard about @Ben Appel ’s upcoming book Cis White Gay?